< Back to posts

Oliver Jeffers & Sam Winston

United Kingdom

Oliver Jeffers is an artist and storyteller whose work takes many forms and whose bestselling picturebooks are loved all around the world. Sam Winston is a fine artist who exhibits widely and whose artists' books are held in the permanent collections of Tate Britain, the British Library, MoMA, Stanford University and many other places.

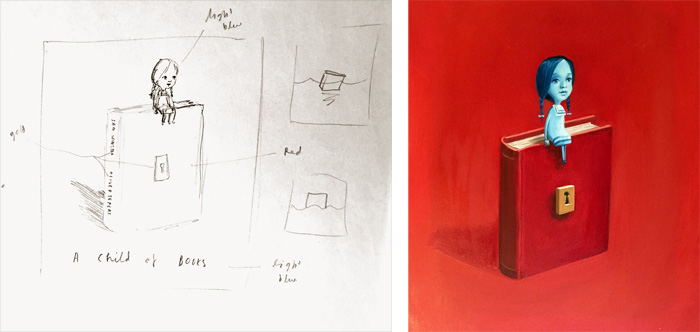

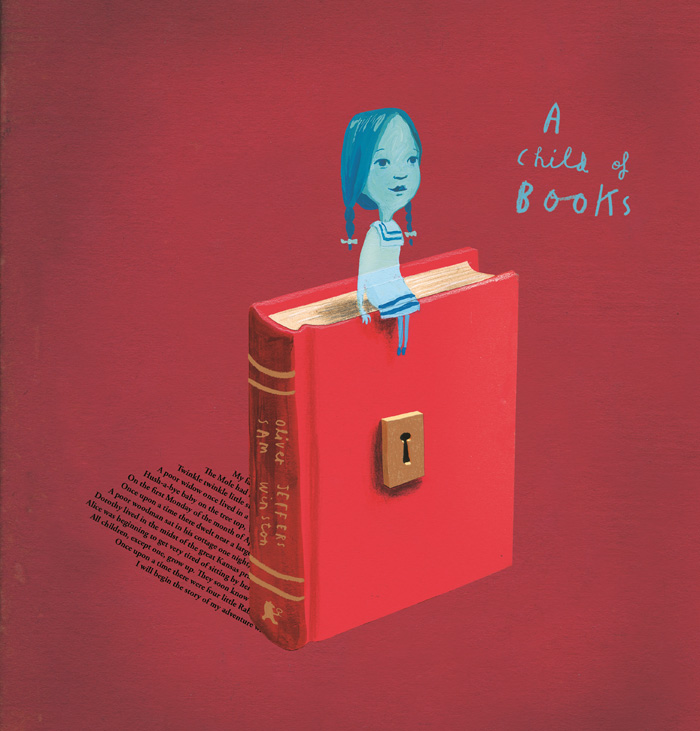

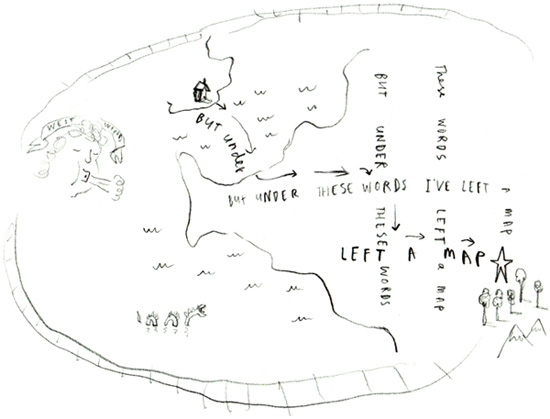

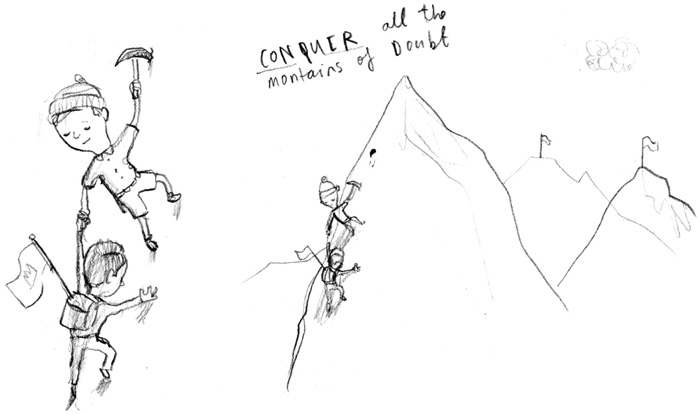

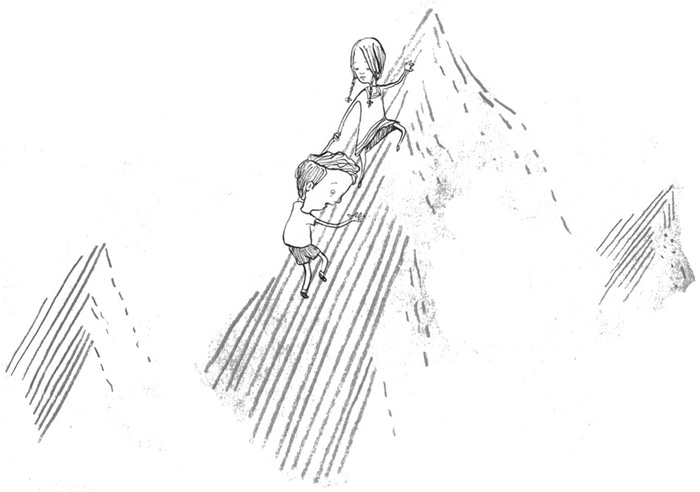

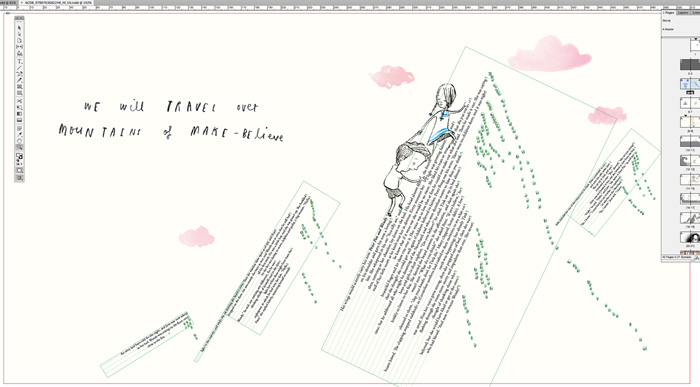

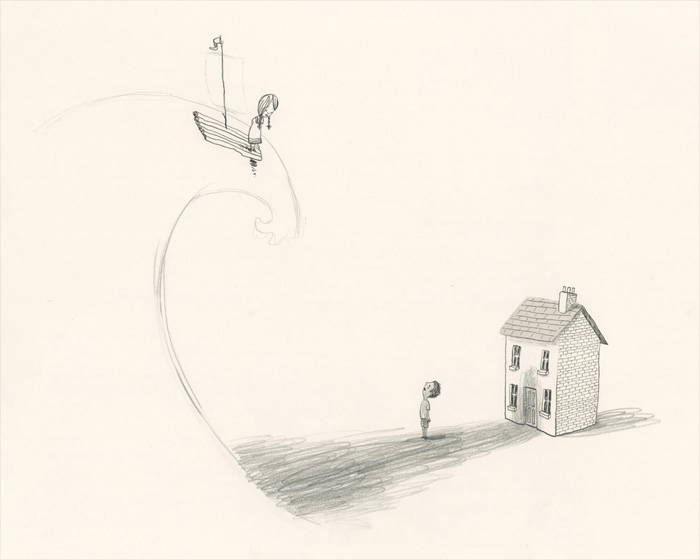

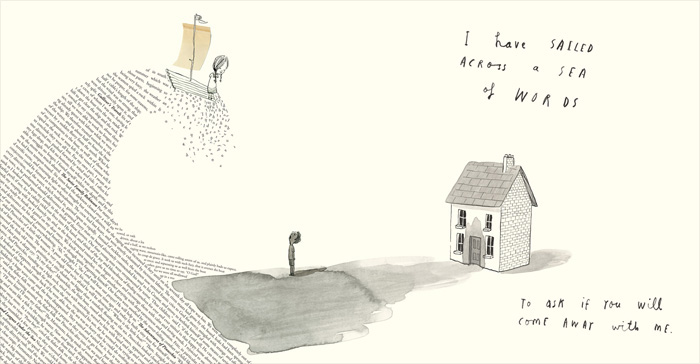

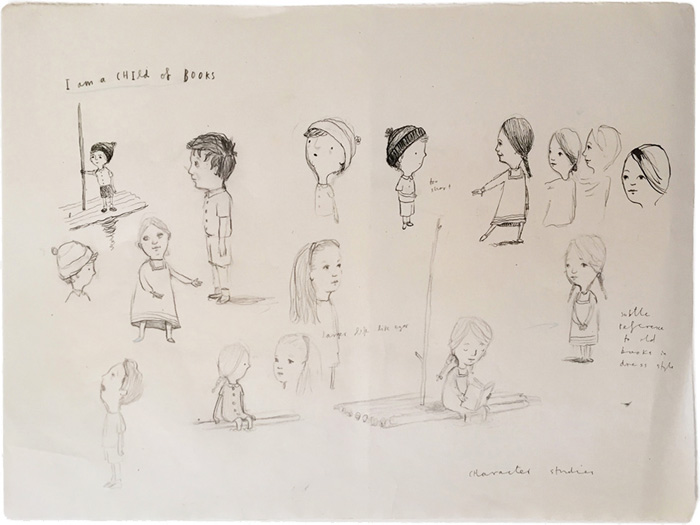

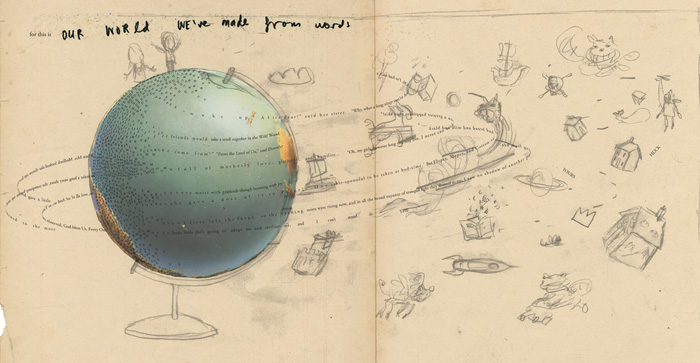

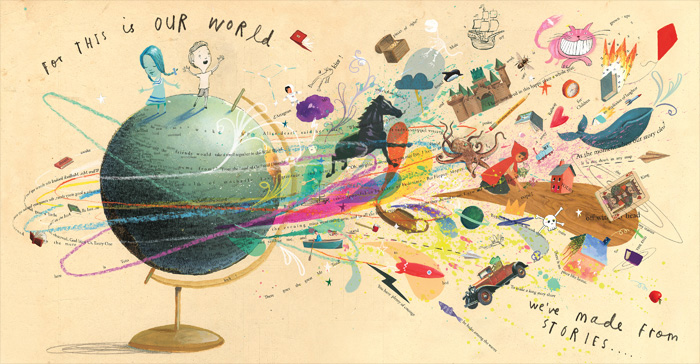

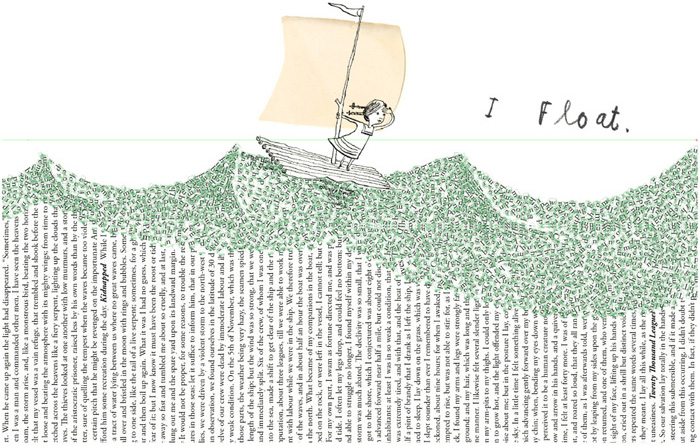

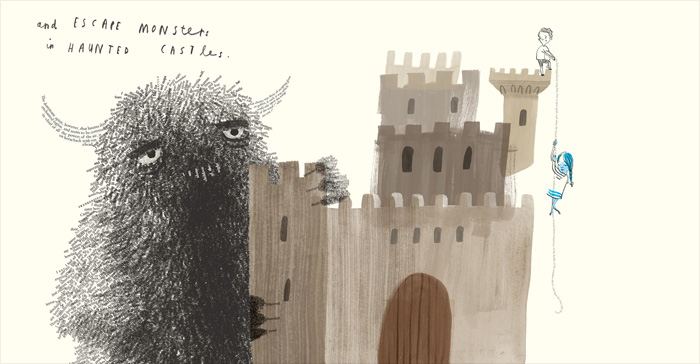

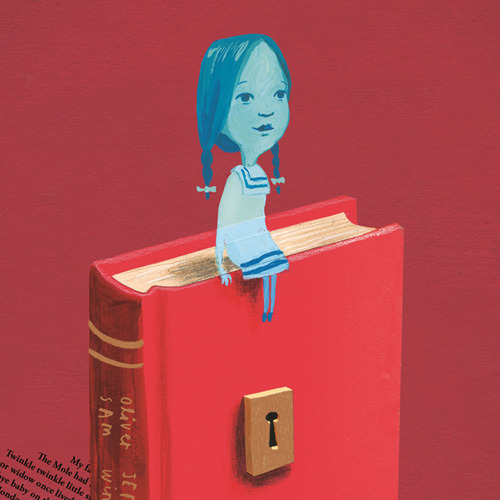

In this post, Oliver and Sam discuss their exciting picturebook collaboration, ‘A Child of Books’. This homage to the power of stories features illustrated characters by Oliver and landscapes which Sam crafted from excerpts from classic children's stories and lullabies.

Oliver and Sam have an online chat...

Oliver: Apparently I'm logged in as someone different.

Sam: Are you going to tell me that you're actually in charge of the whole economy of Azerbaijan and if I give you my bank details I'll be rich?

Oliver: Are you there? Hello? Testing, Testing. One, Two.

Sam: Yep. That's better.

Oliver: I'm on my computer now rather than my phone.

Sam: Ahh, okay.

Oliver: The question mark button doesn't work on my phone, which would have made the conversation fairly one sided.

Sam: That is important as how would you ask anything? You could just use exclamations and make many outlandish statements.

Oliver: This is a criticism my wife makes of me constantly! Okay, let's begin... Hi Sam. So, what are we supposed to talk about for our readers at the Picturebook Makers blog?

Sam: Hello Mr. Jeffers. I think I get to ask you hard questions and you come up with funny yet insightful answers.

Oliver: And vice versa?

Sam: Absolutely, minus the insight and humour. So, do we start at the beginning, middle, or end?

Oliver: Eh... the end? We finished making a book! It took us nearly five years but we did it. Eventually.

Sam: I think that's because we're easily distracted/too excited by many beautiful ideas – hence the long time to complete – but the journey was mightily enjoyable and perhaps the most important part I think. In one sense that book is finished, but we're still motoring along with ideas and stories. Personally I think all of making is process and every now and again a full stop appears in the form of a book or exhibition.

Oliver: Can you remember how it started?

Sam: How did we meet? The first words of hello were on the Internet I presume, but we first sat down face to face in London in 2011 after a friend – Sam Summerskill – thought we would get along handsomely and introduced us. Do you remember what we chatted about?

Oliver: We did. Sam (the other Sam) reckoned we'd get along mightily, and showed me some of your work. I studied typography in art college, but I'd never seen anyone doing anything like you were, and was very intrigued. I probably picked your brain about that a bit, and we probably shared stories about Sam (the other Sam). What I really remember was a few hours later, as we were leaving, it felt like I'd always known you. Anyway, I think somewhere either that day, or in the next few days, we decided we should work on a project together. Although it was not immediately obvious what kind of format that would take.

Sam: I looked back through those emails and we were going to fill shop windows with words/stories (don't know where that went?!). But yes, I was interested in the fact that you did picture books and had a contemporary art practice – and I think that was something we discussed – broad tastes and how creative practice didn't make distinctions between genres – rather staying true to what felt most interesting. And on that foundation I got a real strong sense of trusting you. That's rare I think. To open up what you do and share your practice – to take both compliments and criticism and incorporate it into something you put your name to. But within a few hours, my sense was that we trusted one another with each other's art. Definitely.

I think from there we began to grow a project from a previous text of mine called ‘Orphan’.

Oliver: We definitely came to the conclusion that it should be a picture book fairly quickly. It seemed to make the most obvious sense that characters I created would inhabit a world of type you created. Though what that type should be and what those characters should be was not immediately obvious.

Yes, we took our next cue from an old project of yours called Orphan, about the idea of a character who lives inside books. And it was there that the project really began in earnest. I think we got the meat and bones of the general direction down fairly well after our next meeting, but at that point we hit the most obvious of obstacles – namely, the geographic border between us: the Atlantic Ocean, and what became the first of several points of stagnation. If we weren't both together in the same room, this project tended to get sidelined in favour of other more pressing things. I think it went that way for a few years.

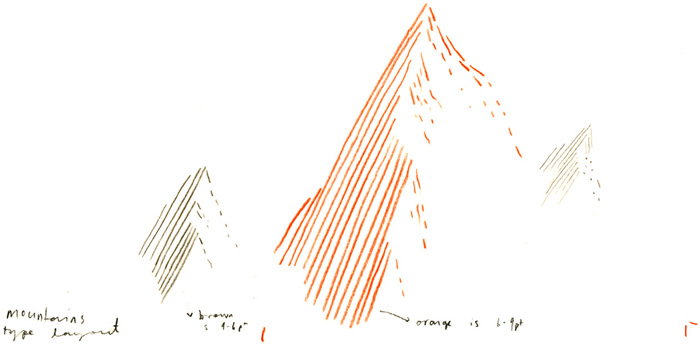

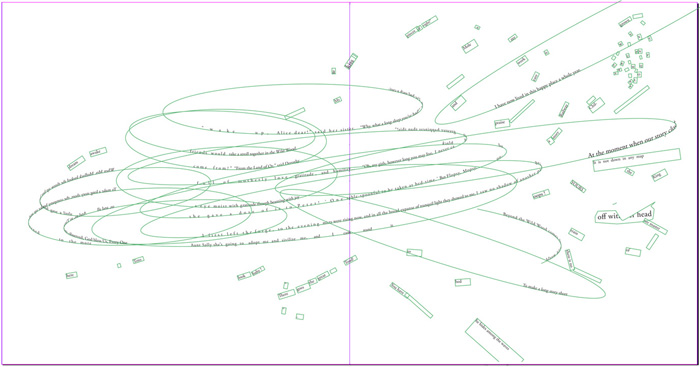

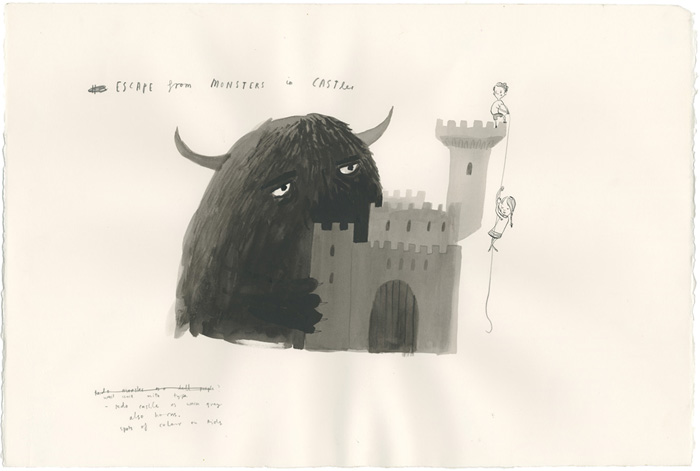

Sam: A lot of the progress came when we were in the same space together – because of the nature of the images. The work became increasingly layered and entwined, with us working in many mediums and formats. Oliver, you could work in pen ink/pencil/collage, then it would be transferred to me and I would take it into InDesign or Photoshop, sometimes going between each format multiple times. The files for this alone became a labyrinth.

Oliver: One of the reasons I thought it would be a good idea to get a publisher involved perhaps earlier than we were ready, was because I thought a third party deadline might kick our arses into gear a bit, and force us to dedicate the time to really figuring it out. Which worked!

Sam: I think the result works. I think it's a compliment that it became almost impossible on certain images to distinguish who did what. I also think that marries very well with the ethos of the book – since we were paying homage to multiple authors across multiple generations. A lot of projects say ‘it was collaborative’, but I really do think this project took the idea of collaboration and fully explored it down to some interesting roots.

Oliver: Yeah, I think it's confusing people slightly to say we both wrote it, and both illustrated it.

Sam: If you want to be fully true to authorship: Lewis Carroll also wrote it.

Oliver: Though he was fairly sensitive to criticism. He'd throw up an awful stink if he didn't think his genius was being fully respected. Not sure I'd collaborate with him again!

Sam: Yeah, but he did have one pill that makes you smaller... and one pill that makes...

Oliver: Anyway, as you've said before, it's difficult to say where this project really began. And also, where it will end.

Sam: I am fully up for questioning the notions of authorship – I think our brains are magpies and we are constantly taking words and pictures from our environments and personal histories. Words and images that weren't ours to begin with but ones that we are happy to lay claim to if we stick them together in a nice order!

Oliver: I agree. No one creates anything in a bubble.

Sam: Except for this chat – these words appear in a nice blue bubble.

[Oliver and Sam are using the Messages app]

Oliver: We could veer off here on a tangent between the difference between influence and plagiarism... where in my opinion, inspiration is where you observe, then digest, then create, and mostly forget where all the little bits came from. Plagiarism is where you know exactly where something came from and lift wholesale. Which, now that I think about it, is exactly how we have used the texts in A Child of Books! Though I suppose that's technically homage, as we aren't trying to pass off Lewis Carrot's words as our own.

Sam: Absolutely. I am not saying that plagiarism is anything good either! I think an author knows when they haven't had a good idea and they are being sloppy, and just encroaching on another's idea. You can tell how they talk about it – everything sounds cliché. I think original work makes new thoughts and that has a real sense of excitement to it.

Lewis Carrots!

Oliver: Did I type that? It must have been autocorrect.

Do you think autocorrect is a good thing for the future of education? Is the choice between reading proper spelling that's autocorrected, or incorrect spelling that's been sloppily typed?

Sam: I think William Burroughs would be pleased – it's taken the cut-up technique to a new level.

Oliver: One more big question each?

Sam: Sounds good. So Oliver – you've made a lot of picture books over a decade now. Where do you think this fits into your oeuvre? And broadly speaking, where do you see picture books heading in the next 10 years?

Oliver: Well, this book is obviously a departure for me. I have collaborated before, but not quite like this. For the first Crayons book, I collaborated with an editor, and didn't meet Drew [Daywalt] until after it was done. For Imaginary Fred, I collaborated with an author, but it was more straightforward: my bringing visuals to Eoin Colfer's text. With the second Crayons book, Drew took the concept to a certain point, then we sat together with the editor in my studio and came up with a bunch of characters together. But this project is the first where the lines truly blur as you say. Because the nature and feel of this book is so different for me too, I wanted to break away from my normal style where, as Eoin Colfer says, I draw like a drunk one-eyed monkey. I wanted to create something that felt more timeless.

So as far as oeuvre, I think this is an important book and a real milestone in my career. Which leads me into where I think books are going in the next 10 years...

I think people were worried about the future of books with the dawn of digital publishing and the potential for technology to disrupt the way we make or read books. But I do not think that is of concern. Yes, new cool things will continue to be produced, but not at the expense of books. Humans have enjoyed the physical object of the book for thousands of years and we are not about to set them down. And our book is basically about a love of literature we both share with a huge percentage of the population (I was about to say English speaking – but the rate at which foreign language publishers are prepared to translate this made me retract that!)

They say that children reject their parents' values and embrace their grandparents' – and there may be some truth to that, which may explain some of the current trends in fashion, music, and food culture...What we have attempted to do with this book is almost to stick a pin in modern picture books' culture, having been shaped by generations of storytellers that have come before. So, rather than get lost in computer games and apps, I believe there is a real and insatiable appetite to enjoy stories. And as we have both discussed at length, stories are hugely important to our identities. So where will picture books go in the next 10 years? The same direction they have always been going. And I hope we will still be there, along for the ride.

Sam: Great answer to a hard question. Sorry. You can ask me a stinker too.

Oliver: Oh I'll think of one.

Sam: Ask me what the square root of 36 is.

Oliver: What's the capital of Outer Mongolia?

Also, what is the square root of 36?

Sam: What is the square root of 36? – Ulaanbaatar

What's the capital of Outer Mongolia? – 6

Oliver: Okay, your question: This is your first picture book, though, perhaps unbeknown to your new audience, by no means your first book. What are your first impressions of the picture book industry, and are picture books something you'd like to continue to explore? Want an easier one? What's for your lunch?

Sam: Cheese sandwich and packet of crisps – and now onto, “what's for lunch?”

Oliver: I've often thought of the industry as a cheese sandwich and packet of crisps before.

Sam: So far, I am fascinated by the picture book industry. I have had the relative luxury of making artist books for 15 years, which has afforded me nearly complete creative control in my projects, which has really helped my practice mature. I think that's why you and I worked well together, Oliver – we both have been making for many years and it meant there wasn't so much of our egos to deal with.

That, combined with the incredible good fortune to collaborate with someone who is a master of their craft – it was an honour to watch how skilled you were around narrative and compositional decisions. That lead to a very fortunate entry into the world of picture books – and in that sense, I have loved it and am truly humbled that it's come out the way it has.

Yet I also think the industry has got a pretty hard edge coming from an artist's perspective. Within the art and poetry world, audiences are smaller and more intimate. You can expect certain levels of literacy and it's expected that you take risks. My biggest surprise here was the number of similar books that have to be created to keep an industry solvent – once a trend takes off you can be sure to see 50 pastiches of it by the next season... In the long term that creates a real challenge for creatives, as there is far less incentive to take risks and explore ideas.

As to whether I will continue to explore? Absolutely. My words and images have certainly been very much welcomed by Oliver, Walker and Candlewick. In a word, it's been an honour to work with these people.

Sam: Now what?

Oliver: I forgot what the question was, but that sounds coherent.

Right. Think we are done. I'm away for lunch. Thanks Sam.

Sam: Pleasure – I mean it.

Oliver: Me too. See you on the road!

A CHILD OF BOOKS. Copyright © 2016 by Oliver Jeffers and Sam Winston. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA on behalf of Walker Books, London.

A Child of Books

Oliver Jeffers & Sam Winston

Walker Books (UK) & Candlewick Press (USA), 2016

In this inspiring, lyrical tale about the rewards of reading and sharing stories, a little girl sails her raft ‘across a sea of words’ to arrive at the house of a small boy. There she invites him to come away with her on an adventure.

Elegant illustrations by Oliver Jeffers are accompanied by Sam Winston's astonishing typographical landscapes, beautifully shaped from excerpts from classic children's stories and lullabies.

- English: Walker Books (UK) — Candlewick Press (USA) — Walker Books (AUS)

- French: Editions Kaléidoscope

- French Canadian: Editions Scholastic Canada

- German: Mixtvision Verlag

- Spanish: Andana Editorial

- Catalan: Andana Editorial

- Galician: Patasdepeixe Editora

- Dutch: Uitgeverij Hoogland & Van Klaveren

- Many more languages are in negotiation